Due to a recent change in our pharmacy software system, the process for submitting refill requests online has now changed.

Our previous mobile app and your current login credentials will no longer work.

Please click the Patient Portal tab to begin the new process.

Thank you for your patience during this transition.

Get Healthy!

- Posted January 26, 2026

Esophageal Cancer: What It Is, Symptoms, and How It’s Treated

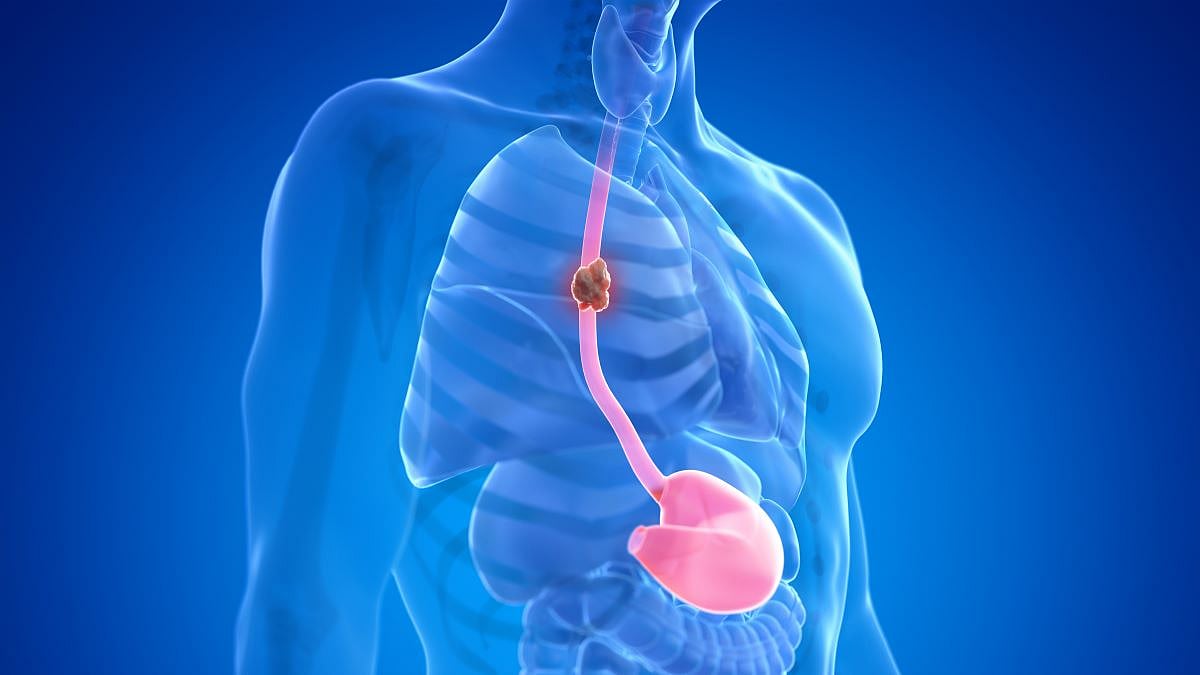

Esophageal cancer is a tumor that forms inside your esophagus, the passageway through which food and water travel from your mouth to your stomach.

This tube starts in the back of your throat, goes through your neck and connects with your stomach in the abdomen. The wall of the esophagus is about a quarter-inch thick and floppy, like the peel of a banana.

Typically, the cancer starts on cells lining the inside of the esophagus and then grows deeper through the wall towards the outside.

What causes esophageal cancer?

Like most cancers, multiple factors can increase a person’s risk, but most people with the risk factors do not develop esophageal cancer. Because the tumors start on the inside of the esophagus, chemicals that irritate the lining are thought to contribute to the risk. The classic example is chronic reflux of stomach acid and bile up into the esophagus.

Patients with reflux often have symptoms of heartburn, but, interestingly, around a quarter of patients with reflux have no symptoms.

Barrett’s esophagus, which is a change in the type of cells that line the esophagus where it joins the stomach, is a change that increases risk for future cancer.

Other factors that increase a person’s risk include obesity, particularly in patients who carry most of the extra weight in their belly, alcohol use, and smoking. Some forms of esophageal cancer are genetic and run in families.

Cancer can be more common in patients with other chronic diseases of the esophagus, such as a rare disorder called achalasia, in which the esophagus does not empty properly.

Patients with these risk factors should discuss screening with their doctor, as they may be able to undergo an internal examination of the esophagus (screening endoscopy) at the same time as their colonoscopy.

Symptoms

The opening of the esophagus limits the size of the food we can swallow. Tumors that grow in the esophageal wall make the opening smaller, and food begins to stick on the way down, which is one of the most common symptoms.

The tumors can also create painful ulcers, which can cause pain when eating and drinking. The ulcers can also be irritated by acid reflux.

Therefore, new symptoms of heartburn, or a change in the severity of heartburn, should prompt patients to discuss with their primary care provider. Many patients will start to eat less because of the symptoms and lose weight.

The earliest forms of esophageal cancer, when the tumor is only in the very first layer of the inside of the esophagus, do not cause symptoms.

These are the hardest to find, because patients don’t know they have a problem, but have the highest cure rates. Researchers are looking for ways to find patients at high risk for esophageal cancer so they can be tested and identified before they develop symptoms.

How is esophageal cancer diagnosed?

Patients whose food often gets stuck are first evaluated with an esophagram, a test in which patients drink a liquid that will show up on an X-ray and highlight any narrowing in the esophagus. Upper endoscopy, which involves inserting a flexible camera into the esophagus through the mouth while the patient is asleep, allows the gastroenterologist to examine the esophageal lining.

Tumors appear as discolorations, ulcers, bumps or narrowings. A biopsy is done by taking tiny pieces of tissue from the abnormal areas. A pathologist then examines these tissues under a microscope, looking for precancer or cancers.

The pathologist can test for genetic changes or proteins the tumor is making that can help the oncology team plan the most effective treatment.

How esophageal cancer is treated

One of the most important factors determining esophageal cancer treatment is how deeply the tumor is growing into the wall of the esophagus.

If we think of the layers of wall of the esophagus as a cake, the frosting is on the inside.

If the tumor is only in the frosting layer, called the mucosa, the cancer can usually be eliminated simply by getting rid of that layer at the tumor site. Using the upper endoscopy camera, the gastroenterologist can cut, freeze or burn the innermost layer and potentially cure the patient without making an incision.

This is by far the easiest for patients and our preference, but because patients with earliest-stage cancers typically have no symptoms, these are the hardest patients to find.

Once the tumor grows deeper into the wall (the spongy part of the cake), the tumor cells can spread to lymph nodes, and most patients will require more extensive treatment.

This may require surgically removing a portion of the esophagus. Because this makes the esophagus shorter, the stomach can then be pulled up to meet the esophagus, typically in the upper chest or neck — a procedure known as an esophagectomy.

This is commonly done using minimally invasive techniques, with the largest incision measuring about 2 inches.

Patients often receive treatment before and after surgery using chemotherapy, as well as immunotherapy, a newer treatment that allows a person to use their own immune system to fight their cancer.

Radiation can also be used for certain types of esophageal cancer and can kill cancer cells in the esophagus and lymph nodes. Ongoing research aims to match patients with the treatment plans that are most likely to cure them with the least disruption to their lives.

Once the cancer cells have spread through the bloodstream to a vital organ, like the liver or lungs, the focus shifts to treating the entire body, because the tumor cells can go anywhere the blood goes.

Patients are treated with chemotherapy, immunotherapy or other specialized treatments that take advantage of tumor genetics or proteins the tumor makes.

This has been an area of active research, with many new treatments becoming available recently and more expected if research continues.

Living with esophageal cancer

Depending on the stage of the esophageal cancer, treatment can range from a single outpatient upper endoscopy to a combination of treatments, including surgical removal of a portion of the esophagus, known as an esophagectomy. Having an esophagectomy can be life-changing, as well as lifesaving.

While the vast majority of patients return to work and are able to resume an active lifestyle, and those who love to eat can enjoy restaurants, there are clear changes. After an esophagectomy, patients walk around with roughly a soda can’s worth of fluid in the part of the stomach that has been moved into the chest. If they lie flat, the fluid can roll back into the back of the throat and they can choke on it.

As a precaution, patients must always keep their heads elevated 30 degrees, even while sleeping. They tend to eat four smaller meals instead of three. That being said, most patients are able to return to a very high quality of life despite these adjustments.

I have esophagectomy patients who swim, bike and enjoy a wide range of active lifestyles, but they must always be mindful of their new anatomy.

Why research is so important in esophageal cancer

A breakthrough in screening for esophageal cancer could completely change the cancer journey for this group of patients. The key way cancer screening saves lives is by finding cancers before they become dangerous, which usually means before patients have symptoms.

For this reason, many research teams are working to figure out which patients would benefit the most from screening, as well as trying to develop tests that are easier on patients and cheaper.

Realizing that not every esophageal cancer can be caught early, researchers are also working on more effective treatments that are less disruptive to patients’ lives.

It is critical that we continue to support esophageal cancer research so the battles with cancer today can help bring us a better way for fighting the cancer tomorrow.

About the expert

Daniel J. Boffa, MD, is a Professor of Thoracic Surgery at Yale School of Medicine. He earned his medical degree from the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine with honors, his MBA from the Heller School of Social Policy and Management at Brandeis, and is a Board-Certified Thoracic Surgeon. He has received numerous awards and recognitions for clinical skills, research and education, including the Dr. Charles H. Bryan Clinical Excellence Award from the Cleveland Clinic, the Thoracic and Cardiovascular Research Award and the CALGB young investigator award, and the Edward H. Storer education award from Yale and the Hassan A. Naama Award from Cornell. His work has been published in top Journals such as the New England Journal of Medicine, the JAMA Network, and Nature, as well as mainstream media, including the New York Times and the LA Times. He has been interviewed by numerous news outlets including Nature Medicine, Bloomberg News, NBC and National Geographic.